Altered Reality

|

In the Artist’s Statement for her new exhibit, Altered Reality, Kay Grubola explains that she is, “…exploring feminism through the traditions of Celtic mythology using the natural materials that have dominated her earlier work. “ In small-scale sculptures that are nominally jewelry, and more specifically in these examples, rings of such uncommon delicacy and character that they are, “… too fragile for anyone other than a Goddess to wear,” she brings nature into art in a unique fashion. Celtic Goddesses were inextricably tied to the natural world, reinforcing the maternal aspect of humankind’s relationship to the earth, and Grubola’s work reinvigorates this mythology.

In part, these improbable constructions represent the idea that power need not come from extremity of size and scale, but from the tiniest of things. Paternal symbols of power are often grandiose and ostentatious, but channeling the sacred through the maternal requires not monuments but meaningful symbols of true connectivity to the foundation of life: fertility and death – ashes to ashes. As Grubola continues on, “The Goddesses’ powers as warriors, as magical beings, as symbols of fertility, as lovers and mothers are intrinsic to the feminist message of the work. “ Grubola is an artist and independent curator in Louisville, Kentucky who has exhibited nationally and internationally. She was the Executive Director of Nazareth Arts, a regional arts center on the campus of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Kentucky, as well as the Artistic Director of the Louisville Visual Art Association. For 10 years she taught drawing and printmaking at Bellarmine University and Indiana University Southeast. Altered Reality is a two-person show at PYRO Gallery with Kay Grubola and Bette Levy, October 1 – November 15, 2015. Located at 909 East Market Street in Louisville’s NuLu district. |

Double Vision

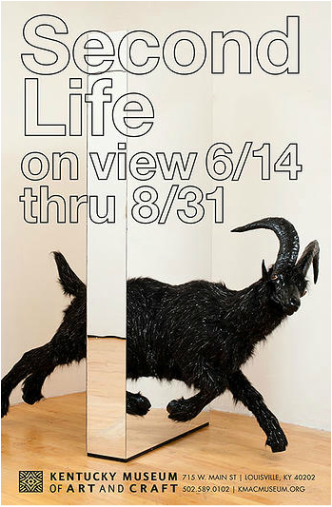

Second Life, Kentucky Museum of Arts and Crafts

Art Review :

“Second Life” and the Taxidermic Gaze, in Louisville

by Joshua Hamilton / August 21, 2014

The group exhibition “Second Life,”explores the use of animal imagery in contemporary art. On view at the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft through August 31, the show, curated by the museum’s associate curator Joey Yates, features taxidermy and other forms of appropriation of animal and insect bodies as a primary strategy for negotiating the relationship of human to animal. Taxidermy helped to create a scientific correspondence in which humans are the subject and animals the objects of study, thus also reinforcing the power relation of hunter and prey: the human interprets the animal in an attempt to capture an anthropocentrically mediated understanding of animal reality.

“Second Life”sets up this historical development of animal representation at the beginning of the show. Several of John James Audubon’s watercolors from The Birds of America—created from Audubon’s own dramatic recreations of scenes using taxidermy—appear next to Katie Parker and Guy Michael Davis’s mixed-media wall piece Zuber’s Menagerie and Damien Hirst’s silkscreen print All You Need Is Love. This initial juxtaposition of work presents a snapshot thesis that the rest of the show examines: the empirical image of the animal in Audubon’s work becomes multiplied by modern systems of mechanical reproduction that consign the animal to the status of a disassociated object of beauty, decoration, and consumerist desire (or more directly, an anthropomorphized reflection of human activity, as seen in a diorama of boxing squirrels by 19th-century taxidermist Edward Hart).

Zuber’s Menagerie places the reproduction of the animal in the context of decorative arts by combining taxidermy, 3D printing, and cut-paper backgrounds based on historic wallpaper design. It creates a productive tension between the aesthetic enjoyment of design, the reproductive objectification of the animal, and the depersonalized violence of taxidermy, to which Hirst’s work responds with the paradoxical superimposition of its own beauty and violence. The diamond dust powdering the upbeat yellow ground in All You Need Is Love brings up notions of glamour and beauty constructed by the privileged economic class. The butterflies seemingly alight on the dazzling surface in an exquisite moment of beauty, until one realizes that the butterflies were trapped and transfixed through death, converted into an object of manufactured consumerism (being one of a series of 50 prints).

Other works in the show augment, personalize, or challenge the role of the depicted animal. An installation by Louisville native Jacob Heustis, Drool, presents the mounted heads of a steinbock, a coyote, a gerenuk, and a javelina—all equipped with hidden tubes that drip water slowly from their mouths. The disconcerting effect of slobbering conveys the sense that the animals possess an uncanny, predatory hunger for the viewer/hunter (whose trophy they supposedly are). Heustis’s estranged taxidermy resists the gaze of the viewer and destabilizes the role of the animal as a passive object of study.

Dwelling No. 7 (Corsican Ram), by New York artist Drew Conrad, expands on this interference of perspective: a ram bursts through the wall of an interior habitation, itself metaphoric of the borders of the interior human life. The manifestation of the ram occasions an apocalyptic alteration of that interior epistemology, and the melded fragments of both worlds in this work reflect larger themes in the show: namely, that the human articulation of animal reality not only does violence to the animal world but can then turn on itself and interrogate the widely accepted, working paradigm of human subject and animal object.

L.A.-based Carlee Fernandez’s work, as seen in Rabbit with Calla Lillies, disturbs the boundaries of the natural world by fusing the vegetal and the animal in installations that appear beautiful at first glance, but reveal a grotesque melding of the two upon closer observation. Kay Polson Grubola makes nature’s iconography specific in her insect assemblages, combining personal narrative, Celtic mythology, and feminist concerns in adornments constructed from insects. The power of the animal world to act as an underlying spiritual and ontological consciousness further reveals itself in Andréa Stanislav’s sculptures, such as Rising, which combine taxidermy and mirrors to couple the viewer’s image with that of the animals, creating a sense of intermingled spirits and deeper consciousness. A mural by University of Wisconsin professor Jennifer Angus, Repeated Warning, is composed of large, dead insects procured from Thailand. The corpses form patterns around a skull, from which a cloud of cicadas issues in a brilliant burst that breaks the design and escapes onto the adjoining wall.

Finally, humankind is the specimen in several works. German artist Jochem Hendricks has synthesized lost or amputated appendages into diamonds that are worn by the individual, making him both the subject and object of fetishized preservation. Left Defender Right Leg, for example, is an assemblage that includes a diamond synthesized from the amputated leg of a soccer player, and Oleg’s Ear, which comprises a diamond stud earring and a photograph of Oleg wearing the stud, which was made from part of that same ear.

In The Mouse by Bigert and Bergström, the viewer sits in a cagelike cedar box—a reference to the cedar chips used in science lab mouse cages—while viewing a film that explores humans’ relationship with mice through science and religion: scenes of mice mercilessly used in science experiments are juxtaposed with those of complete reverence and convivence in Eastern religions, further blurring the boundary between human and animal.

Joshua Hamilton lives in Southern Indiana, teaches Spanish, and researches Spanish visual poetry and neo-avant-garde art. He completed his PhD in Spanish at Indiana University in 2013.

“Second Life” and the Taxidermic Gaze, in Louisville

by Joshua Hamilton / August 21, 2014

The group exhibition “Second Life,”explores the use of animal imagery in contemporary art. On view at the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft through August 31, the show, curated by the museum’s associate curator Joey Yates, features taxidermy and other forms of appropriation of animal and insect bodies as a primary strategy for negotiating the relationship of human to animal. Taxidermy helped to create a scientific correspondence in which humans are the subject and animals the objects of study, thus also reinforcing the power relation of hunter and prey: the human interprets the animal in an attempt to capture an anthropocentrically mediated understanding of animal reality.

“Second Life”sets up this historical development of animal representation at the beginning of the show. Several of John James Audubon’s watercolors from The Birds of America—created from Audubon’s own dramatic recreations of scenes using taxidermy—appear next to Katie Parker and Guy Michael Davis’s mixed-media wall piece Zuber’s Menagerie and Damien Hirst’s silkscreen print All You Need Is Love. This initial juxtaposition of work presents a snapshot thesis that the rest of the show examines: the empirical image of the animal in Audubon’s work becomes multiplied by modern systems of mechanical reproduction that consign the animal to the status of a disassociated object of beauty, decoration, and consumerist desire (or more directly, an anthropomorphized reflection of human activity, as seen in a diorama of boxing squirrels by 19th-century taxidermist Edward Hart).

Zuber’s Menagerie places the reproduction of the animal in the context of decorative arts by combining taxidermy, 3D printing, and cut-paper backgrounds based on historic wallpaper design. It creates a productive tension between the aesthetic enjoyment of design, the reproductive objectification of the animal, and the depersonalized violence of taxidermy, to which Hirst’s work responds with the paradoxical superimposition of its own beauty and violence. The diamond dust powdering the upbeat yellow ground in All You Need Is Love brings up notions of glamour and beauty constructed by the privileged economic class. The butterflies seemingly alight on the dazzling surface in an exquisite moment of beauty, until one realizes that the butterflies were trapped and transfixed through death, converted into an object of manufactured consumerism (being one of a series of 50 prints).

Other works in the show augment, personalize, or challenge the role of the depicted animal. An installation by Louisville native Jacob Heustis, Drool, presents the mounted heads of a steinbock, a coyote, a gerenuk, and a javelina—all equipped with hidden tubes that drip water slowly from their mouths. The disconcerting effect of slobbering conveys the sense that the animals possess an uncanny, predatory hunger for the viewer/hunter (whose trophy they supposedly are). Heustis’s estranged taxidermy resists the gaze of the viewer and destabilizes the role of the animal as a passive object of study.

Dwelling No. 7 (Corsican Ram), by New York artist Drew Conrad, expands on this interference of perspective: a ram bursts through the wall of an interior habitation, itself metaphoric of the borders of the interior human life. The manifestation of the ram occasions an apocalyptic alteration of that interior epistemology, and the melded fragments of both worlds in this work reflect larger themes in the show: namely, that the human articulation of animal reality not only does violence to the animal world but can then turn on itself and interrogate the widely accepted, working paradigm of human subject and animal object.

L.A.-based Carlee Fernandez’s work, as seen in Rabbit with Calla Lillies, disturbs the boundaries of the natural world by fusing the vegetal and the animal in installations that appear beautiful at first glance, but reveal a grotesque melding of the two upon closer observation. Kay Polson Grubola makes nature’s iconography specific in her insect assemblages, combining personal narrative, Celtic mythology, and feminist concerns in adornments constructed from insects. The power of the animal world to act as an underlying spiritual and ontological consciousness further reveals itself in Andréa Stanislav’s sculptures, such as Rising, which combine taxidermy and mirrors to couple the viewer’s image with that of the animals, creating a sense of intermingled spirits and deeper consciousness. A mural by University of Wisconsin professor Jennifer Angus, Repeated Warning, is composed of large, dead insects procured from Thailand. The corpses form patterns around a skull, from which a cloud of cicadas issues in a brilliant burst that breaks the design and escapes onto the adjoining wall.

Finally, humankind is the specimen in several works. German artist Jochem Hendricks has synthesized lost or amputated appendages into diamonds that are worn by the individual, making him both the subject and object of fetishized preservation. Left Defender Right Leg, for example, is an assemblage that includes a diamond synthesized from the amputated leg of a soccer player, and Oleg’s Ear, which comprises a diamond stud earring and a photograph of Oleg wearing the stud, which was made from part of that same ear.

In The Mouse by Bigert and Bergström, the viewer sits in a cagelike cedar box—a reference to the cedar chips used in science lab mouse cages—while viewing a film that explores humans’ relationship with mice through science and religion: scenes of mice mercilessly used in science experiments are juxtaposed with those of complete reverence and convivence in Eastern religions, further blurring the boundary between human and animal.

Joshua Hamilton lives in Southern Indiana, teaches Spanish, and researches Spanish visual poetry and neo-avant-garde art. He completed his PhD in Spanish at Indiana University in 2013.

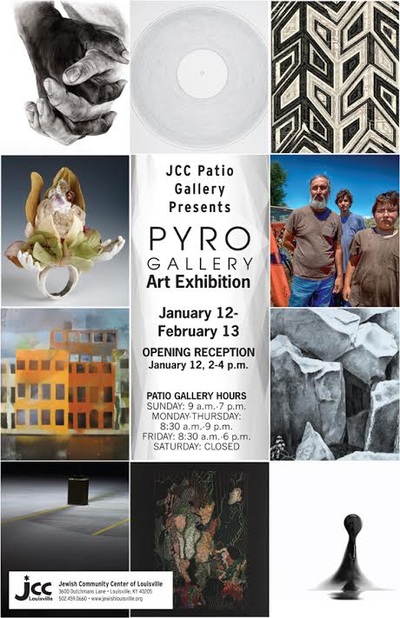

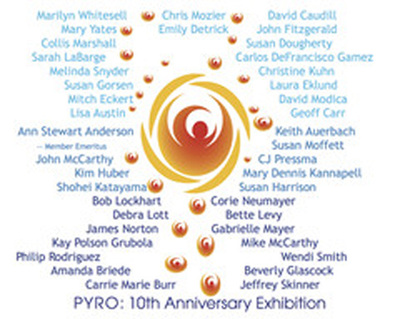

Two Concurrent Exhibitions Celebrating PYRO Gallery's 10th Anniversary

Patio Gallery and PYRO Gallery

PYRO is in a New Space and Bette Levy Invited Some Friends to Come Along

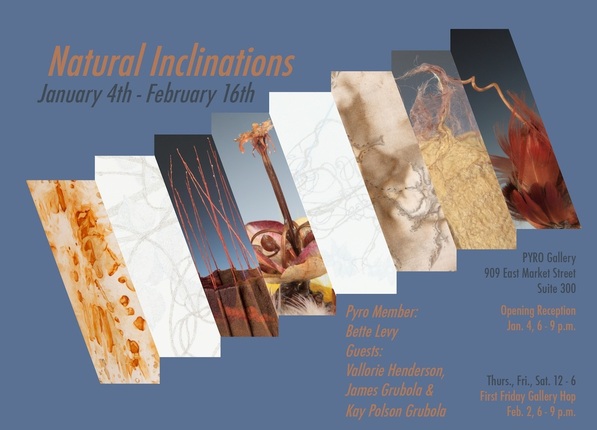

Natural Inclinations

Pyro Gallery

A review by Keith Waits.

Entire contents are copyright © 2013 Keith Waits. All rights reserved

Among the many treasures to be found in the First Trolley Hop of the New Year, the first exhibit of entirely new work from the recently relocated PYRO Gallery may (arguably) be the highlight. The space has been open with a collection of member’s work for a few weeks now, but a new exhibit, “Natural Inclinations”, features the work of PYRO member Bette Levy and 3 friends from outside of the group, Vallorie Henderson, Kay Polson Grubola, and James Grubola.

The new space, in the Sign-A-Rama building at 609 East Market, is smaller and broken up to include a smaller room filled with work apart from the primary exhibit, and an alcove off to one side. Exposed ductwork hovers over a rough-finish concrete floor and the impact of the room itself is diametrically opposed to the old PYRO gallery, which, while beautiful, was also a less adaptable space than this more grounded and cozy environment.

Those nooks are used to good effect with this combination of two and three-dimensional work. Ms. Levy’s large wall pieces occupy the walls opposite the entrance, and the largely earth tone palette and sumptuous visual textures invite you in to the space. In Mosquito Creek in Flood, careful stitching belies the elemental feeling of the piece; so suggestive is it of animal hides hung inside a primitive domicile. The metaphor to the natural world carries through her other work and, in fact, the work of all the artists in the show.

The felted, machine stitched vessels of Vallorie Henderson sweep across the room, mostly on pedestals, while Kay Polson Grubola’s colorful and eccentric insect and seedpod constructions move you into the tight end of the alcove, where you are subtly forced into close inspection of James Grubola’s graceful and detailed drawings.

Relationships among the materials and color reinforce this flow, so that the viewer’s eye discovers connections of tactile surfaces in the fiber pieces, then vivid color forming an alliance between the sensual felt vessels and the hand-painted organic forms of Ms. Grubola’s delightfully impractical jewelry. The final bridge is more thematic, also an important unifying element here, as Mr. Grubola’s beautifully intricate gold and silverpoint drawings examine thickets and vines that could be home to the previous artist’s bugs and seed casings.

On PYRO’s website, each artist describes the layering in their work, and that deliberate build up of the physical and visual texture brings home how the natural world is embraced both in their subjects and in their materials. Bette Levy’s largely abstract work utilizes walnut inks and techniques that stain or burn the materials, while Ms. Henderson employs natural materials in work that follows Cherokee tribal traditions. The organic elements long found in Kay Grubola’s work are here newly transformed into sparkling, hand-painted jewelry, most spectacularly presented in a custom designed (by the artist) wooden case that stands on angled, legs suggestive of the limbs of one of her insect forms. Placed into impossible juxtaposition on rings and pendants, similar forms are the most obvious example of layering, while James Grubola’s patient development of lines drawn with a medium consisting of precious metals complete the journey through nature on an elemental level.

PYRO Gallery is open 12-6 PM on Thursday, and Friday and Saturday or by appointment. The gallery is open late during opening receptions and First Friday Gallery Hop. Admission to PYRO is free and open to the public.

Natural Inclinations: Bette Levy and Friends

January 4 -February 17, 2013

PYRO Gallery

909 East Market Street

Louisville, KY 40202

502-587-0106

pyrogallery.com

Natural Inclinations

Pyro Gallery

A review by Keith Waits.

Entire contents are copyright © 2013 Keith Waits. All rights reserved

Among the many treasures to be found in the First Trolley Hop of the New Year, the first exhibit of entirely new work from the recently relocated PYRO Gallery may (arguably) be the highlight. The space has been open with a collection of member’s work for a few weeks now, but a new exhibit, “Natural Inclinations”, features the work of PYRO member Bette Levy and 3 friends from outside of the group, Vallorie Henderson, Kay Polson Grubola, and James Grubola.

The new space, in the Sign-A-Rama building at 609 East Market, is smaller and broken up to include a smaller room filled with work apart from the primary exhibit, and an alcove off to one side. Exposed ductwork hovers over a rough-finish concrete floor and the impact of the room itself is diametrically opposed to the old PYRO gallery, which, while beautiful, was also a less adaptable space than this more grounded and cozy environment.

Those nooks are used to good effect with this combination of two and three-dimensional work. Ms. Levy’s large wall pieces occupy the walls opposite the entrance, and the largely earth tone palette and sumptuous visual textures invite you in to the space. In Mosquito Creek in Flood, careful stitching belies the elemental feeling of the piece; so suggestive is it of animal hides hung inside a primitive domicile. The metaphor to the natural world carries through her other work and, in fact, the work of all the artists in the show.

The felted, machine stitched vessels of Vallorie Henderson sweep across the room, mostly on pedestals, while Kay Polson Grubola’s colorful and eccentric insect and seedpod constructions move you into the tight end of the alcove, where you are subtly forced into close inspection of James Grubola’s graceful and detailed drawings.

Relationships among the materials and color reinforce this flow, so that the viewer’s eye discovers connections of tactile surfaces in the fiber pieces, then vivid color forming an alliance between the sensual felt vessels and the hand-painted organic forms of Ms. Grubola’s delightfully impractical jewelry. The final bridge is more thematic, also an important unifying element here, as Mr. Grubola’s beautifully intricate gold and silverpoint drawings examine thickets and vines that could be home to the previous artist’s bugs and seed casings.

On PYRO’s website, each artist describes the layering in their work, and that deliberate build up of the physical and visual texture brings home how the natural world is embraced both in their subjects and in their materials. Bette Levy’s largely abstract work utilizes walnut inks and techniques that stain or burn the materials, while Ms. Henderson employs natural materials in work that follows Cherokee tribal traditions. The organic elements long found in Kay Grubola’s work are here newly transformed into sparkling, hand-painted jewelry, most spectacularly presented in a custom designed (by the artist) wooden case that stands on angled, legs suggestive of the limbs of one of her insect forms. Placed into impossible juxtaposition on rings and pendants, similar forms are the most obvious example of layering, while James Grubola’s patient development of lines drawn with a medium consisting of precious metals complete the journey through nature on an elemental level.

PYRO Gallery is open 12-6 PM on Thursday, and Friday and Saturday or by appointment. The gallery is open late during opening receptions and First Friday Gallery Hop. Admission to PYRO is free and open to the public.

Natural Inclinations: Bette Levy and Friends

January 4 -February 17, 2013

PYRO Gallery

909 East Market Street

Louisville, KY 40202

502-587-0106

pyrogallery.com

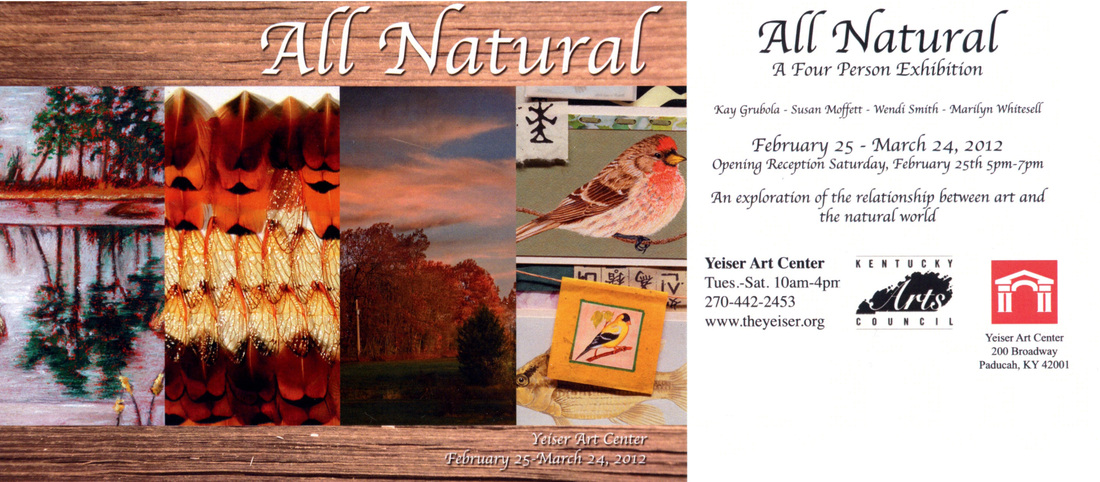

All Natural Four-Person Exhibition

Yeiser Art Center Paducah, Kentucky

Kay Polson Grubola, Susan Moffet, Wendi Smith & Marilyn Whitesell

February 25-March 24, 2012

Opening Reception Saturday, February 25, 5:00-7:00pm

http://theyeiser.org/exhibitions.html

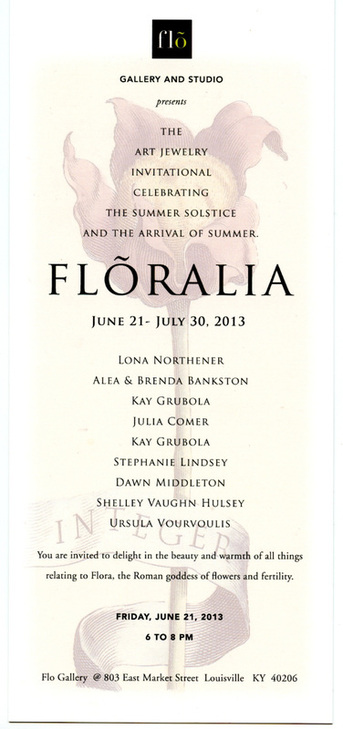

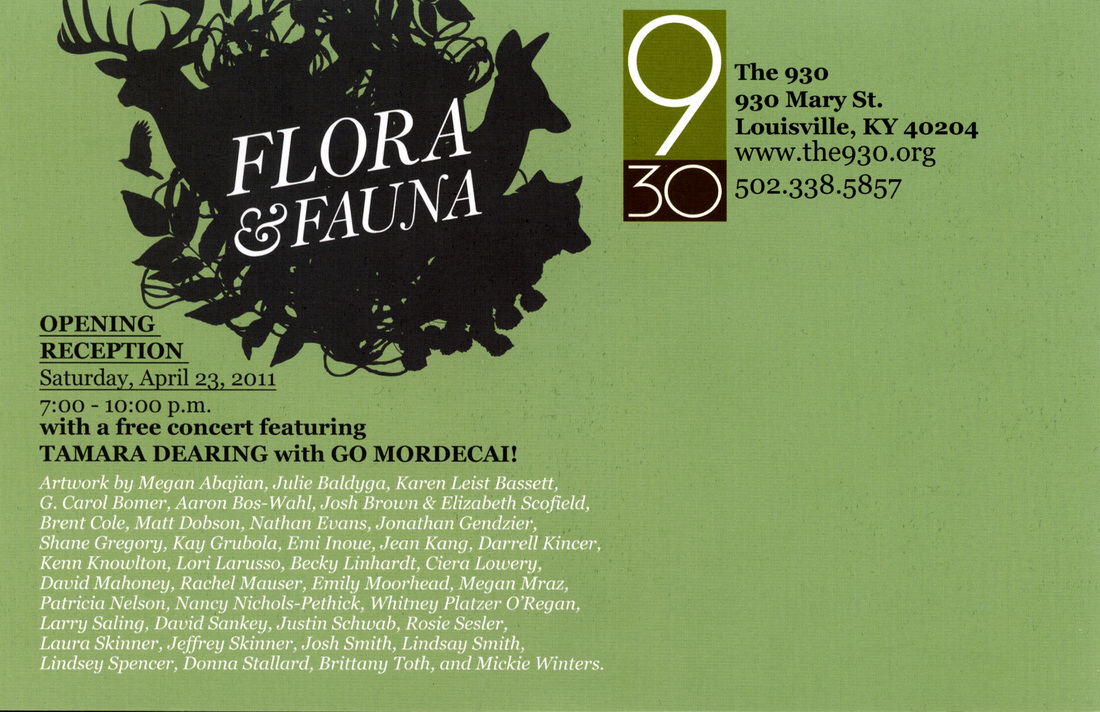

Flora & Fauna Exhibition

Best In Show Award Kay Grubola

Studio San Giuseppe Exhibition Announcement

(Cincinnati, OH) – The Studio San Giuseppe Art Gallery at the College of Mount St. Joseph announces the opening of Collective Memories running from September 18 through October 21, 2011. The exhibition offers a captivating look at the contemplative art works by three Louisville master artists: Mary Ann Currier, and Jim and Kay Polson Grubola. An Artists’ Reception will be held on Sunday, September 18, from 1:30-4:30 p.m. The public is cordially invited to meet the artists, view their work and enjoy light refreshments.

It was recognized very early in her life that Mary Ann Currier was good in art. At age 84 she is working as hard and diligently as ever, still producing truly extraordinary work. Her dramatically realistic still lifes are sought after by museums and collectors. She was the subject of a documentary episode in the KET/PBS series Kentucky Muse called “Master of Still Life” that aired in 2008. Her keenly observed large-scale oil, oil pastel and charcoal compositions of fruit, onions, roses, tableware, and other ordinary objects, have made her a revered figure in contemporary still life painting. The carefully considered compositions, acute observation and deft skills in painting and drawing have generated a stunning and prolific collection of art works. She says in the documentary, “For me, art is a way of being alive in the world.”

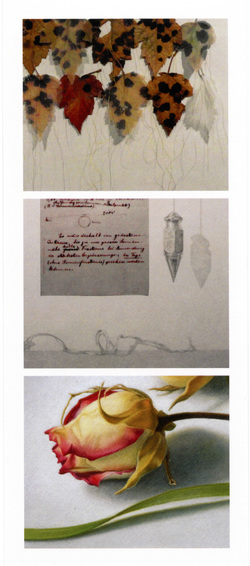

Equally masterful are the works of Jim and Kay Polson Grubola. Jim, a current professor of drawing at the University of Louisville, has been producing exquisite drawings, many in silver and gold point, for several decades. The delicate lines enhance the atmospheric qualities of a newer interest involving science and astronomy. Incorporating vellum overlays of scientific notes and calculations, along with measuring devices, a plumb bob, and more recently included ladders that suggest an intellectual measure of the vastness between celestial objects, his intimate drawings echo an evolving human presence in our longtime quest for knowledge of distant space.

Kay Polson Grubola’s likewise exquisite assemblages of earthly objects, like feathers, cicada wings, pine needles or shells, speak of a very close examination of what is literally around us, essentially right in front of us or under our feet. Her elegantly defined compositions, many incorporating a geometric grid, expose the unique beauty of these delicate natural objects, seemingly identical, in repetitive rows that force the viewer to intently examine each for minute similarities and differences. Even the manner of attaching these fragile objects to a ground reveals her mastery of a subtle, restrained rhythm and a visual harmony across a measured surface. All of the assemblages have an accompanying haiku, allowing the power of the written word to add further dimension to the presence of each piece.

There is an understated, seemingly golden thread of compatibility that runs through the work of all three of these Louisville master artists, each possessing a highly polished skill of very keen observation, and a very acute intellectual ability to juxtapose rather common objects in a manner that piques the visual, emotional and intellectual senses of the viewer. Perhaps it is as the title that suggests genuinely shared Collective Memories, spoken or intuitive, making this exhibition so truly captivating and so quietly contemplative for the viewer. This is a must see! The exhibition runs through October 21.

It was recognized very early in her life that Mary Ann Currier was good in art. At age 84 she is working as hard and diligently as ever, still producing truly extraordinary work. Her dramatically realistic still lifes are sought after by museums and collectors. She was the subject of a documentary episode in the KET/PBS series Kentucky Muse called “Master of Still Life” that aired in 2008. Her keenly observed large-scale oil, oil pastel and charcoal compositions of fruit, onions, roses, tableware, and other ordinary objects, have made her a revered figure in contemporary still life painting. The carefully considered compositions, acute observation and deft skills in painting and drawing have generated a stunning and prolific collection of art works. She says in the documentary, “For me, art is a way of being alive in the world.”

Equally masterful are the works of Jim and Kay Polson Grubola. Jim, a current professor of drawing at the University of Louisville, has been producing exquisite drawings, many in silver and gold point, for several decades. The delicate lines enhance the atmospheric qualities of a newer interest involving science and astronomy. Incorporating vellum overlays of scientific notes and calculations, along with measuring devices, a plumb bob, and more recently included ladders that suggest an intellectual measure of the vastness between celestial objects, his intimate drawings echo an evolving human presence in our longtime quest for knowledge of distant space.

Kay Polson Grubola’s likewise exquisite assemblages of earthly objects, like feathers, cicada wings, pine needles or shells, speak of a very close examination of what is literally around us, essentially right in front of us or under our feet. Her elegantly defined compositions, many incorporating a geometric grid, expose the unique beauty of these delicate natural objects, seemingly identical, in repetitive rows that force the viewer to intently examine each for minute similarities and differences. Even the manner of attaching these fragile objects to a ground reveals her mastery of a subtle, restrained rhythm and a visual harmony across a measured surface. All of the assemblages have an accompanying haiku, allowing the power of the written word to add further dimension to the presence of each piece.

There is an understated, seemingly golden thread of compatibility that runs through the work of all three of these Louisville master artists, each possessing a highly polished skill of very keen observation, and a very acute intellectual ability to juxtapose rather common objects in a manner that piques the visual, emotional and intellectual senses of the viewer. Perhaps it is as the title that suggests genuinely shared Collective Memories, spoken or intuitive, making this exhibition so truly captivating and so quietly contemplative for the viewer. This is a must see! The exhibition runs through October 21.

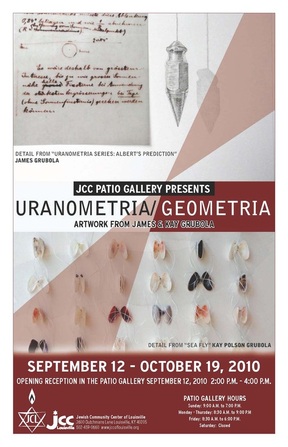

Uranometria/Geometria

Artwork by James and Kay Grubola

A review by Margaret Lockwood

The Jewish high holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur provide the perfect context for Uranometria/Geometria, new work by husband and wife artists James and Kay Grubola, on exhibit at the Jewish Community Center Patio Gallery from September 12 through October 19, with artists’ opening September 12, 2-4 p.m.

The “Urano” of the title refers to the sky, while “Geo” refers to Earth. The shared suffix “metria” refers to measurement. The title of the show is a bit daunting; their work is not. Together, these two artists have created a deeply personal meditation that invites viewers to step closer to consider the frame of human existence—the sky above and the Earth below.

James Grubola’s drawings take viewers and point them toward the heavens. The focal piece is Uranometria: Ursa Minor, a drawing executed in silver and gold point. It is the only one of his pieces that lacks a ladder, but his three other motifs are present: a scientist’s notes and calculations, a measuring device, and a plumb bob. These have been the tools of celestial scientists for centuries, and each generation of discoveries has brought with it new ways of calculating the distances as a means of interpreting the universe.

The lines of this drawing are pale, almost ghostly, and when you look closer, they almost seem too fine to have been drawn by a human hand. Although the graphite lines of his other pieces might be thicker, darker in color, a small piece of velum with scientific jottings overlays a portion of each drawing and dims the background with a layer of fog and shadow, suggesting that no matter how hard we try, no matter how precise the calculations or how great the intellect guiding them, our vision will always be imperfect because it cannot take in the whole—only its fleeting essence.

The graphite drawings include one feature not present in the silver and goldpoint image: a ladder. Each successive drawing shows the tools of the scientist becoming more sophisticated, the body of knowledge expanding, and the mathematics and measurements more complicated. Yet the ladders remain fixed in design. They are primitive, with rungs lashed to side poles by sinew or rope. Grubola says he got interested in the idea of ladders months ago, thinking about “risk ladders” as a tool in decision-making. But those ladders morphed in his mind to become the “distance ladders” of astronomers, with each rung representing an intellectual progression in the quest to determine the distances to and between celestial objects.

However, as each of Grubola’s drawings shows the evolving science of astronomy, the ladders serve as a visual counterpoint, a constant reminder: no matter how complex the science, it’s still human beings devising the scheme. But there is also a conversation among scientists in Grubola’s drawings—from Galileo and Ptolomy to Einstein and Edwin Hubble, and the title of each piece points us to the individual, “Albert’s Prediction,” and “Isaac’s Proposal,” a reference to Isaac Newton’s plans for a type of telescope. This intimacy underscores the humanity behind their questing. After all, these are just men, caught up in wonder.

The strong gravitational pull of the present keeps artist Kay Grubola rooted to earthly subjects and objects that seem, on the surface at least, more humble: feathers, shells, beetle wings, pine needles, nature’s refuse. What makes this work extraordinary is the artist’s eye and Grubola’s ability to force us to examine the uniqueness of the particular and the importance of the mundane. Unlike James Grubola’s subjects, Kay’s are right in front of us. The distance of Light Years doesn’t obscure our seeing, and yet, we don’t. Look here, she seems to be saying. Right beneath your feet, there is mystery a plenty. And her questions are no less profound because they come from the temporal world we all inhabit.

Where her husband’s titles were personal, Kay Grubola’s move us toward abstraction, and most force us to examine what is left behind when the life force has been extinguished—and what we do with that which is left behind. Among the elements she incorporates in her work are feathers collected decades ago by her uncle, a gameskeeper on a Scottish estate. Some of the assemblages also include drawn lines and most feature intricately stitched and knotted silk threads—human hands reassembling found objects and arranging them into a statement.

Take “Haiku to Those Who Die Young.” Red maple leaves on tiny stems have been turned to black velvet by a sudden frost. They are beautiful—another thing entirely than they were in life, before the catastrophic event. In “The Beautiful Necessity of Flight,” pheasant feathers and cicada wings are arranged in distinct rows whose edges blend seamlessly together—insect and bird merged by the shared memory of flight. By fixing our attention on the commonplace, the discarded, the refuse of the natural world, Kay Grubola’s overarching subjects affirm the questing that infuses her husband’s work: Pay attention! This is our universe—but only for a minute.

In all ways, the exhibit is about a marriage—two unique individuals looking at our cosmic environment from vastly different points of view, yet describing what they see through the shared confidence in form and design. Above all, the work of James and Kay Grubola celebrates the profound power of the human mind as it strives to create order and to take meaning for our lives from the universe around us.